What is Markov Chain?

Markov chains, also known as discrete-time Markov chain, get its name after the Russian mathematician Andrey Markov, are mathematical systems that hop from one “state” (a situation or set of values) to another.

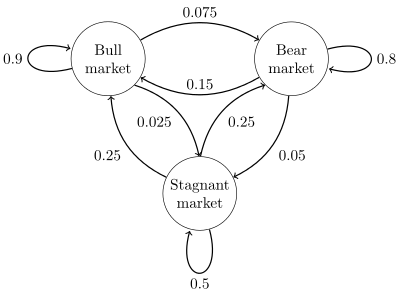

To motivate this discussion, we start with a simple example: consider a stock market with 3 possible states: Bull market, Bear market, and Stagnant market, which will be denoted by 0, 1, 2, respectively. It is possible to transition randomly from any state to another per second according to the following scheme:

The state space for this process is given by \(\mathcal{S} = \{0, 1, 2\}\) and we denote by $X_t$ the state of the market at time \(t = 0, 1,2,\ldots\) which is called the state of the process at time \(t\).

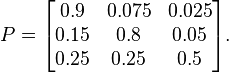

Let \(p _ {ij}\) denote the probability of going from position i to position j in one step. In the above stock market example, Bull market can change to Stagnant market with a possibilty of 0.025, which suggests \(p_{02} = 0.025\). The numbers \(p_{ij}\) are called the one-step transition probabilities of the process. Denote by P the transition matrix whose entries are the \(p _ {ij}\), and we have for the stock market example:

We are interested in the following questions:

- Starting from state 0, what is the expected time taken to reach state 2?

- Starting from state 1, what is the probability of being in state 2 at timet? Does the probability converge as \(t \rightarrow \infty\), and if so, to what?

Markov Property

In a Markov chain, the future depends only upon the present, NOT upon the past.

The above random walk is a Markov in the sense that it is memoryless as used for the exponential distribution and we can “forget the past”:

\[\begin{align} P( X _ {t+1} = s _ {t+1} | X _ t = s _ t , X _ {t-1} = s _ {t-1}, \ldots , X _ 0 = s _ 0 ) = P( X _ {t+1} = s _ {t+1} | X _ t = s _ t ) \end{align}\]Although this equation has a very complex look, it has a very simple meaning: The distribution of our next state, given our current state and all our past states, is dependent only on the current state. It is clear that the stock market above does have this property;

Convergence Property

In typical applications we are interested in the long-run distribution of the process, for example, the long-run proportion of the time that we are at position 2. For each state i, define

\[\begin{align} {\pi}_i = \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} \frac{N_{it}}{t} \end{align}\]where \(N_{it}\) is the number of visits the process makes to state i among times \(1, 2,..., t\). In most practical cases, this proportion will exist and be independent of our initial position \(X_0\). (There are mathematical conditions under which this is guaranteed to occur, but they will not be stated here.)

Intuitively, the existence of \(\pi_i\) implies that as t approaches infinity, the system approaches steady-state, in the sense that

\[\begin{align} \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} P(X_t = i) = \pi_i \end{align}\]Though we will again avoid discussing mathematical conditions for this to occur, the point here is that this last equation suggests a way to calculate the values $\pi_i$, as follows.

First note that

\[\begin{align} P(X_{t+1} = i) = \sum_k P(X_t = k) \cdot p_{ki} \end{align}\]Then as \(t \rightarrow \infty\) in this equation, intuitively we would have

\[\begin{align} \pi_i = \sum_k \pi_k p_{ki} \end{align}\]Letting \(\pi\) denote the row vector of the elements \(\pi_i\), these equations (one for each i) then have the matrix form

\[\begin{align} \pi = \pi P \end{align}\]Note that there is also the constraint

\[\begin{align} \sum_i \pi_i = 1 \end{align}\]This can be used to calculate the \(\pi_i\). For the stock market model as above, assume that the initial state of the stock market is given by \(\[0.1 , 0.2 , 0.7\]\), we implement the following code

def markov():

init_array = np.array([0.1, 0.2, 0.7])

transfer_matrix = np.array([[0.9, 0.075, 0.025],

[0.15, 0.8, 0.05],

[0.25, 0.25, 0.5]])

restmp = init_array

for i in range(25):

res = np.dot(restmp, transfer_matrix)

print i, "\t", res

restmp = res

markov()

with output as follows:

0 [ 0.295 0.3425 0.3625]

1 [ 0.4075 0.38675 0.20575]

2 [ 0.4762 0.3914 0.1324]

3 [ 0.52039 0.381935 0.097675]

4 [ 0.55006 0.368996 0.080944]

5 [ 0.5706394 0.3566873 0.0726733]

6 [ 0.58524688 0.34631612 0.068437 ]

7 [ 0.59577886 0.33805566 0.06616548]

8 [ 0.60345069 0.33166931 0.06487999]

9 [ 0.60907602 0.32681425 0.06410973]

10 [ 0.61321799 0.32315953 0.06362248]

11 [ 0.61627574 0.3204246 0.06329967]

12 [ 0.61853677 0.31838527 0.06307796]

13 [ 0.62021037 0.31686797 0.06292166]

14 [ 0.62144995 0.31574057 0.06280949]

15 [ 0.62236841 0.31490357 0.06272802]

16 [ 0.62304911 0.31428249 0.0626684 ]

17 [ 0.62355367 0.31382178 0.06262455]

18 [ 0.62392771 0.31348008 0.06259221]

19 [ 0.624205 0.3132267 0.0625683]

20 [ 0.62441058 0.31303881 0.06255061]

21 [ 0.624563 0.31289949 0.06253751]

22 [ 0.624676 0.3127962 0.0625278]

23 [ 0.62475978 0.31271961 0.06252061]

24 [ 0.6248219 0.31266282 0.06251528]

We can see that from \(t = 18\),stock state begins to converge to \([0.624 , 0.312 , 0.0625]\) whereas the later on minor change is due to floating computation of the machine. In fact, the above phenomenon is true for any other initial states.